Firstly, if you're in the midst of Nanowrimo and you're in a breathless hurry, here's the simplest and quickest and most efficient name site I've found:

behindthename.com

I've browsed online name sites for years and somehow never managed to reach behindthename in a search, so I'm reposting it here. It's thorough, it gives ethnicity and meaning, and it displays in a nice long list to scroll through so you don't waste have your writing time clicking next and waiting for the screen to load. And, best of all, it lets you easily search by top letter in the top bar.

Step 1: choose a different first letter for all your characters.

Step 2: Pick your favorite by sound, spelling, meaning, or cultural origin (preferably all 4)

Now, must you have different first letters for all characters? This is common writing advice (a la Orson Scott Card and many others). At first I was skeptical, but I started paying attention. As a reader, did I really find it confusing when two main characters had same-letter first names? Was it really that much easier to read fast when all I had to identify was the first letter? Actually... yes. In a few recent books, where multiple characters' names began with A or D, and they were not only in the same scene but having rapid-fire conversations, the sort of banter you want to read quickly without mistaking names... yes. It slowed me down a little. Not much, but those first letters made it just a little more difficult to read, and if you want your readers to have an easy time, why bog them down with such an easy fix? Burn your difficulty points elsewhere.

The easier your book is to read, the more people will read it.

So! Now I make alphabet lists, with names by first letter, and when naming a new character, choose a letter not yet taken.

This only matters if characters' names will apper side by side in the text. No need to fuss if they're in alternating points of view from Sri Lanka and Siberia.

While you're analyzing names:

• Vary the length and number of syllables between characters. Sam, Rachel, Jackalope, and Al-Faridi just look better and more interesting together than Sam, Ray, Jack, and Al. (Or, far worse, Sam, Sal, Sarge, and Seth.)

• The literal appearance of the name on paper is the first visual readers will have of your character. Bob seems solid; Valinesse seems ornate and slippery. Probably a villain. Probably why so many villain names include the snake-hiss-sneaky sounds of the letters S, V, and Z.

• The ethnic background of a name will form our picture of a character more clearly than any description you give. Choose wisely. This is tricky, especially in American families, where our lineages are thoroughly scrambled. We are mutts. But for sheer ease of readers visualizing a character: if his last name is O'Malley and you describe him once as Hispanic (entirely possible, if his Mom's Venezuelan and his Dad's Irish, and he's got his Dad's last name), then repeat the name O'Malley dozens of times throughout the book… maybe we'll remember he was Hispanic. But that O' in front of the last name is so traditionally Irish, that we also might forget. If you name him Rodriguez, problem solved. Sometimes all we see of side characters is what their name looks like on the page. So if you want us to picture a team of professionals or staff of teachers as racially diverse, choose racially diverse last names, and readers see it with no further description.

Anyway! Where else can you find names?

1) Ethnic registries. If you know your character comes from a certain culture, search it: 'Traditional Pakistani Surnames', or 'Common South Korean first names for girls in 1980', if you know when and where your character was born.

2) Mythology, if you want to add history to a character. The middle name 'Medusa' is bound to foreshadow something about a character's dangerous hair, or dangerous eyes, or turning some life form to stone.

3) A Latin dictionary (or other obscure language), if you want to invent your own name from root words. The Latin for poison is 'venenum'; the meaning could lend a foreboding clue to the means of murder preferred by a villain named V.E. Nenum.

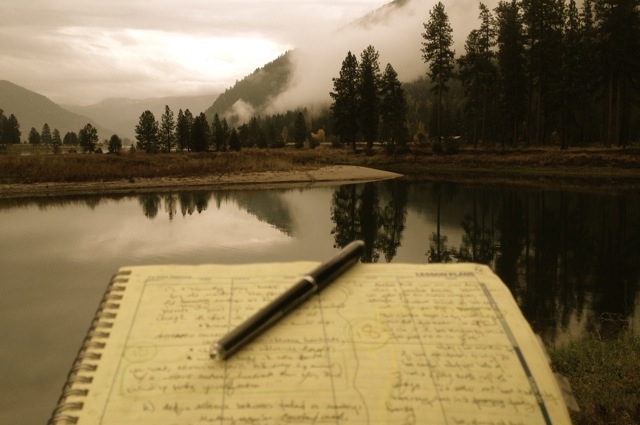

4) And, my personal favorite, because this is also one of my favorite places to write: cemeteries. (to be cont'd.)

Happy writing.

-mlj