Why sketching is like meditating, and why you should try it.

For some people, meditating is hard.

I'm bad at it.

Because, let's be honest, OCD brains loathe doing nothing, and every attempt I've ever made to sit quietly still and think of nothing has ended in failure. My brain says, "What's for dinner?" and "I should be writing," and "I'd rather be reading than writing!" and, "I could devise a magic system based on those cattails," and, "Ooh, how sweet would be it be if a spaceship crash-landed in this bog and you wound up making first contact with an interstellar species amid washed-up reeds and startled frogs and mud-soaked ducklings? That'd be a story. I could write that story."

To which I say, "SHUT UP!" and my brain says, "This is such a waste of time," and I end up more stressed than I started.

So I've never succeeded in meditating, but I still want to try and learn the lesson of meditating, which is essentially: to get out of my own snarled head and notice things. The world is beautiful. I pass by too fast. Without seeing. Without feeling. Without paying attention to details, in the present moment. I want to breathe deep and be able to cancel out all the white noise.

Enter, travel sketching.

Note: you do not have to be able to draw. At all. That's not the point.

Anyway, 'being able to' strikes me as about as useful a term as 'having talent for.' Neither term is useful at all.

'Being able to' and 'being unable to' should be reworded as 'Have learned already' and 'Have not learned yet.'

'Being talented' and 'being not talented' should be reworded as 'Have practiced a lot' and 'Have not practiced enough yet.'

Seriously. Reword the world into skill sets, instead of god-given qualities; it makes everything so much less frustrating. Define all your ambitions by hours of effort instead of assigned labels. Go read THIS AWESOME ARTICLE on why we should stop praising kids with 'You're talented' or 'You're smart' and start praising them with 'You tried really hard'. (Spoiler alert: Kids praised for trying really hard try hard again, and pick challenging puzzles, because they're in control. Kids praised for being talented pick easier puzzles. They're afraid of failure and afraid of losing their label.)

Anyway. I've always disliked the word 'talented', and likewise the term 'gifted', not least because it implies accomplishments were easy, or that just because the same task might be harder for someone else, or take someone else longer, they ought to just give up. Puh-leaze. Like any of us should decide our life's course solely based on aptitude. There are about a zillion things that are easier for me than writing. (In fact, drawing is one of them.) I have a really, really hard time writing. Really hard. It may be easier for a lot of other people. People who aren't so indecisive, who can just nail down a story without second-guessing themselves, or second-guessing their word choice, or a character, or a scene, over, and over, and over. Death to perfectionist brains everywhere: I do so much better when I know there's a right answer, because then I know I can get it perfect, and avoid disapproval, but in fiction there is no right answer. Any story could be anything. Go anywhere. Any planet. Forward or backward in time. Murder. Resurrection. Betrayal. What's the best answer? What's the perfect answer? I don't know! Gah! It drives me bonkers!

The longer I live the more I've started thinking, the things that are hardest for you may be the things you care most deeply about. Those are the things we want so, so badly to get right. Follow your passion, not what you do most easily. Follow what you care deeply about, even if it's hard.

In the end, that is what you'll be best at, because you'll never get sick of trying.

It'll just take forever, because it'll keep seeming like you're never as good as you want to be.

In the meantime, it's good to get out of your head for a while, writers. So if meditation fails you because you just need to be doing something, allow me to suggest a rather extraordinary form of doing something which also focuses your attention, and promotes sitting still, and promotes noticing the insignificant and overlooked details of the world.

I studied abroad in architecture school, and the very excellent professor Peter Kommers required us to do a sketch a day. He also required us to do it in pen. And to do it on site, not from photographs.

This man is a genius. I had no idea what being forced to sit and observe would do to my brain.

Well, I hear you saying, staring skeptically at your screen, Just take photographs. Easier. Faster. This world's all about easier and faster. And clicking a camera shutter is way more efficient than drawing one black line at a time."

You're right. Except, an interesting thing happened. I got back from Italy, and realized I had 3,000 photos and about 50 sketches. Each photo took about three seconds to take; each sketch took at least half an hour. I hardly remembered where I'd taken any of the photographs. But I remembered every single place I'd sketched, so vividly I could taste it. Sometimes the sketches turned out awful. Sometimes it rained. Sometimes I wanted to start over. But the rules had been, we couldn't start over, and we couldn't erase since we were drawing in pen. Sometimes we messed up, but we still had to finish the sketch.

Sometimes we didn't mess up. Sometimes the sketches looked great. About 1 in 5 were lovely; that seemed to be the ratio.

But eventually I realized, getting a perfect sketch wasn't the point.

Not at all.

Not even close.

It's like, being labeled as 'talented' isn't why you do the things you really care about. The point is trying really hard. The point is that while we were sitting there sketching, on the steps in a corner of a piazza, we thought about exactly what we found so special in that scene, and we sat still long enough to care.

The point is not to do many things well, or do as many things as possible in one lifetime.

The point is to care about what you've done.

Photographs capture every detail exactly, but they also capture all details equally, and omit nothing. Oftentimes, looking through those 3,000 photos, I can't remember why I took them in the first place. Maybe I once saw something special in that scene. But amid the other details I can't remember what it was. Maybe I snapped a quick photo while walking, thinking, "Oh, I don't have time to look at that bird (or that crenelation, or that painting, or that garden) now, but I want to remember I saw it, later."

Except, I don't remember it later. Because the things we remember are the things we felt most strongly. And if I didn't stand still long enough to care about it in the first place… it faded into the blur. If I didn't stop to feel something about it in the present, to decide what exactly I found so special about that scene, or that place, or that view, or that moment, I don't remember it later.

Sometimes I think our whole lives are like this.

We hurry in a blur, so fast all we can think about is moving on to the next thing. I remember so, so clearly that while in Italy, I never thought I had time to do a sketch. Never! Not one! I didn't have time to sit still! Not for 30 minutes, not here! I had things to do, I had things to see, I was in Italy, I had to make the most of it, I couldn't waste any time, I had to keep moving, moving, moving! I had a checklist! Every minute of every day, no wasting time!

But now, looking back?

The only things I remember clearly are the times I sat still.

If I pull out one of those sketches and look at it, I can feel the stone steps pressing into my skin. I can read the notes I wrote and remember pigeons roosting on cathedral walls, and when I saw— on one particularly shadowy sketch— the scribbled note, 'I wish there was a way to record the way the fountain echoes off the alley walls', it almost made me cry. I remembered writing that. I remembered hearing that. I remembered a kid laughing as he passed the fountain on his bike, and me waving at his mother, and neither of those things were written or drawn anywhere on the sketch. I remembered.

Why?

Because I'd paused long enough to feel.

We do an interesting thing, while sketching. Or in any art. We transcribe and amplify reality and filter out the unimportant. You can't draw every line, every flower. So you pick one single thing, and draw it in a lot of detail, and leave out the rest. You see a scene and pick your favorite detail. Something that strikes you. Something that makes you feel. And then you focus on it, and even if it's a single blade of grass, I promise you:

The point is not drawing a perfect blade of grass.

The point is that if you follow that old drawing rule of '90% of time spent observing, 10% drawing', you'll notice so many other things you never would have seen if you hadn't stopped and sat and drawn that blade of grass, and taken the time to be still.

Go out and get yourself a cheap sketchbook, something small enough to carry around in your bag. Then get yourself a pen.

No pencils allowed. No erasing. Start with a small thing, just one flower, just one rock. Draw it small to keep yourself from getting overwhelmed. A few inches wide, or two. And write yourself notes in the margins. You don't have draw everything. You don't have to draw the birds singing. You can scribble, "Birds singing up in the branches. Robin? Yes, robin. I hope he doesn't take a dump on my head."

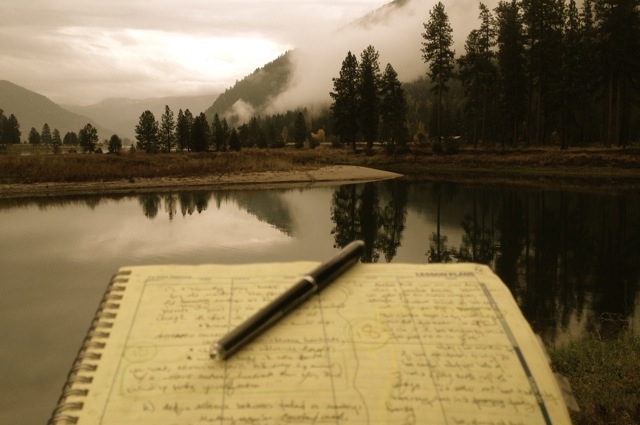

Start with something small, and simple, like these trees that I watched bending in a windstorm on the other side of the river.

Remember, no erasing, and no starting over.

The point isn't worrying about whether or not the lines you've drawn look like what you see.

The point is that if you sit for ten minutes, you ought to spend nine of those ten minutes observing.

The point is to see.

And hey, if you've got an OCD brain like me, and the sort of workaholic personality that feels guilty for sitting still and doing nothing, even for a moment?

You're doing something. You're practicing drawing.

And at the end? Bravo! You've got a sketch.

Meditation for workaholics: travel sketching. An excuse to sit in one place without feeling guilty, and stare at something gorgeous.

"I felt that I owed a debt to the universe that only my attention could repay."

-John Green, The Fault in Our Stars.

Happy sketching.

-mlj